The Derby Silver Company

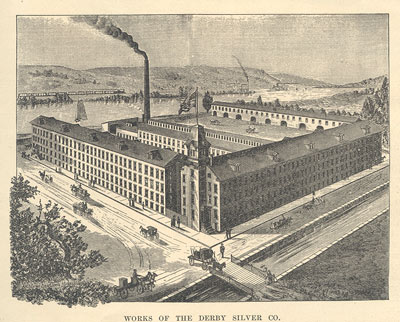

The Derby Silver Company was founded in 1872, and began operations on Shelton’s Canal Street one year later. The company soon outgrew its quarters and constructed a larger building, which still stands on Bridge Street, Shelton, in 1877 near the Housatonic River, overlooking Derby. A number of additions were added in subsequent years. The original Canal Street building was razed when the railroad was built through Shelton in 1888.

The company made toilet articles, mirrors, combs, clocks, brushes, table and flatware, tea sets, children’s cups, loving cups (trophies), candlesticks, fruit baskets, dishes, basically anything which was plated by or made of silver. Special orders were constantly commissioned as well. The factory manufactured items for the Sperry and Hutchins trading stamp stores. The Company was noted for its large line of silver plated toilet ware and an economical line of plated hollowware sold under the popular trademark of the Victor Silver Plate Company.

Showrooms were established in New York City, Chicago, and San Francisco. A considerable amount of silver was shipped to South America. The logo at the time featured an anchor, often with the words “Derby Silver Company” or its initials surrounding it.

In 1898, the plant merged with the International Silver Company, a consortium of Connecticut silver companies. At that time the Derby Silver Company works was known as “Factory B”. Thus, as a rule of thumb, items with the “Derby Silver Company” logo most likely date from the nineteenth century, while items with the International Silver Company logo, either Derby or Factory B, are from the twentieth.

A victim of the Depression, the plant closed in 1933. The Derby Silver Company’s building remains intact on Bridge Street in Shelton. The building had served as an automobile muffler factory, and during World War II manufactured bombsight optics. In 1949 it was bought by the Sponge Rubber Products Company. The Sponge Rubber Products Company was bought out by B.F. Goodrich in 1954. The large smokestack that served the Silver Company was torn down in October of 1961. The building reverted back to the rejuvenated Sponge Rubber Products Company in 1974, and was fortunately far enough away from the subsequent firebombing of the main plant of the SRPC a block south on Canal Street not to be destroyed in the explosion.

The old building was bought by former employees of the Sponge Rubber Company, who formed Housatonic Everfloat, manufacturing foam rubber cushions, mats, and life preservers. Housatonic Everfloat was bought out by a company called Spongex in 1985, which continues similar manufacturing operations in the old Silver Company building to the present day.

Articles manufactured by the Derby Silver Company are still to be found in Derby, Shelton and her sister communities of the Lower Naugatuck Valley, some of which are on public display. Besides the Derby and Shelton Historical Societies, another good source is a book entitled “A Century in Silver 1847-1947, Connecticut Yankees and a Noble Metal” by Earl Chapin May, written in 1947.

Remembering the Derby Silver Company

Originally written August 1998 by Robert Novak Jr. for the weekly newspaper Huntington Herald)

They still stand along Canal Street. Large, brick buildings, built during the American Industrial Revolution, the very nucleus from which sprang forth downtown Shelton. Today they are in sorry shape. Some are deserted or mostly deserted. One is burned out. Some are gone entirely, leaving behind weed and brick strewn lots.

It is hard to imagine sometimes that this was a bustling industrial center, with thousands of people pouring in and out of the factories, many of which had three shifts. The factory whistles or gongs would sound, and the faceless multitudes of workers would stream into the smoke belching plants, perhaps dodging a locomotive that was running along the spur tracks on Canal Street. They would disappear into another world behind the closed doors, only to reemerge when the long shift would end.

While we have pictures of what all the factories looked like from the outside in historical collections and archives, we have precious few pictures of what went on after doors closed behind the last workers for the day. Newspapers aren’t much help, the Derby Transcript often gave detailed, glowing accounts of the workings of the factories without referring much to the people inside. The Evening Sentinel offered better glimpses of factory life, but because many of the descriptions came during times of labor unrest it wasn’t exactly the best time to report on day to day activities inside the factories.

In 1918, Charles C. Smith (1904-1980) turned 14. By law, Smith was eligible to work in Shelton’s factories providing he had parental permission. Since his uncle, Watson Miller, helped found the Derby Silver Company in 1872, and his father served as the factory’s manager, Smith naturally gravitated to this plant on the corner of Bridge and Canal Streets. Smith would later write a book entitled Autobiography of a Connecticut Yankee, in which he would detail his experiences working in the Derby Silver Company.

Working after school and on weekends, Smith labored in the Shipping Department. Among his fellow employees were recent veterans of World War I. Smith earned 5 cents an hour, while the adults were paid from 20 to 25 cents an hour. He recalls “There were no coffee breaks, no time and a half overtime pay, no vacations, and no retirement benefits” in those days.

Smith’s job was to unload wagon loads of box ends. These ends would then be nailed together to make custom-sized boxes for whatever silver shipments were to be made. The trick was to make a box large enough to fit everything but small enough not to leave a lot of empty space. The silver was sent from the shoproom floor to shipping via an elevator. Much of the silver was destined for South America, and was often packed in hay, which was difficult to work with in the summer if one had allergies. The largest boxes weighed 300 pounds when filled. The boxes would be loaded on the horse drawn wagons of the Oates Brothers Trucking Company, where it was hauled to the Derby train station. Oates Brothers’ building still stands at the corner of Wharf Street and Howe Avenue (note – this building has subsequently been torn down).

Smith recalls the busiest times were in the fall, when stores through the United States and South America sought to fill their stocks before Christmas. The Shipping Department would work until 9 PM on Saturdays to keep up with the orders.

Although Smith had entered the workingman’s world, he was still a young boy, and naturally curious. When his department wasn’t busy, he’d wander to other parts of the factory. His father frowned upon this, saying “Suppose all the workmen wandered around as you are doing- you have no right to do this- go back to the Shipping Department”. After awhile, Smith recalls his wanderings became a game of “hide and seek” from his father, and he was often aided by men in other departments in avoiding his father.

The Engraving Department was where one of the Silver Company’s best engineers, Mr. King, worked. Smith remembers King would cover an item’s surface with talc, and trace a design in it. He then “…would select one of his many sharp-pointed tools and with what appeared to be reckless abandon, he would cut away on the surface of a product worth as much as $1500 (a lot of money for a boy making 5 cents an hour!) …When he finished cutting all his lines and curves, he washed off the talc exposing a masterpiece”.

For a few months Smith worked in the Casting Department, located on the ground floor. Molten white metal was poured into two sections of molding. They were then clamped together and allowed to harden, forming the desired mold. Smith recalls “It was a hot place in the summer because the metal pots were heated with coal fires. In those days we had no eye shields or safety glasses to protect us from the splattering of hot molten metal. We were furnished with eye shields to protect our clothing (from catching fire)”. The ground floor also housed the Machine Shop and the Slow Hydraulic Press Departments, supervised “…by a very stern Mr. Welch”.

Above the Hydraulic Press Department was the Spinning and Turning Department, where huge blocks of Arkansas gumwood was turned into bases for prize cups (trophies), also known as “loving cups”. Also large, flat disks of metal on a rotating surface was formed into prize cups, children’s cups, pitchers, and other items which would later be plated with silver.

The work of the various departments all converged on the third floor Soldering Department. This large department would join various pieces together to make a wide variety of products. Smith spent another summer in this department, “…under the kind and helpful direction of Mr. Haynes. My work consisted of soldering the two white metal ends and two sides of fruit bowls together and then solder the base…I held a piece of solder between my teeth, brought two mating castings together by hand under a small Bunsen Burner flame”. A mild sulfuric acid was used, which created “…quite an objectionable odor”. Smith worked ‘piecework’ that summer, which meant he was paid in accordance with his output, a common practice in Valley factories, especially the textile ones. “Needless to say, I was not wandering around the factory while on that job. I often wondered later in life if there wasn’t some deal between Mr. Haynes and my father to keep me busy”.

After soldering, the products were smoothed, then put on racks and moved by hands to cleaning tanks by the Plating Department. They were then dipped in vats containing either gold or silver. Often the valuable metal would drip, so every few years the floors would be torn up and sent to Handy Harmon Company in Bridgeport, where the gold and silver would be reclaimed from the wood. The products at this point had a dull finish, so they were sent to the Buffing Department to be shined. The dust would cause the men in this department to be black by the end of the day. There were no showers to wash the stuff off, just long common sinks. The product would be cleaned and dried, then stamped with the trademark anchor and product number, and wrapped in special soft protective paper. It would then be sent into storage, and from there the Shipping Department.

When demand for silver fell during the Depression, the Derby Silver Company began turning out lower cost pewter ware. Smith’s father took his chief designer to New York museums to copy some of the designs used by Paul Revere. The pewter sold well, but it was not enough to rescue the floundering Silver Company, which closed in 1933. Smith states “This laid off many loyal men of 40 to 50 years of service, also Father with 28 years. No retirement plan was provided for any of these men who had given the best years of their life to the company. Some went on the WPA (Works Progress Administration) and a few found other work”.Today the Derby Silver Company still stands on the south side of Bridge Street, like a silent sentinel to Shelton’s industrial past. It is currently occupied by Spongex, which manufactures foam rubber products. With the exception of losing a tower that once graced its roof, the exterior is remarkably unchanged. On certain days, you can almost hear the ghosts of the workers of long ago filing through the front doors and vanishing into the closed, disappeared, and almost forgotten world described by Charles Smith.